News and Notes from The Johnson Center

Strategies for Meltdowns

JCCHD | Wed, October 25, 2017 | [Applied Behavior Analysis][Autism Treatment]You may hear the terms tantrum and meltdown used synonymously, but did you know that they mean different things? A meltdown is as an episode that occurs when the nervous system is overwhelmed by social, cognitive, linguistic, emotional, or sensory experiences. The meltdown is a release of tension that typically comes with a big reaction. The person loses control and explodes; this is an involuntary response. They cannot control it—intense emotions take over, and children don’t have the coping skills to manage them. They lose cognitive control and are unable to process and think. When a meltdown happens, recovery is slow, up to 15-20 minutes once the stressor is removed. Adults are not immune to meltdowns, either. They may have learned more strategies to better regulate their nervous systems, but getting overwhelmed happens to everyone at times.

A tantrum, on the other hand, is a deliberate response to frustration. This is a learned behavior, and the child has the cognitive control to choose to do it. Tantrums happen because they have been reinforced—they have worked in the past to get the child something. Tantrums can become emotional blackmail—parents and others give him whatever he wants so that he doesn’t have a tantrum. Recovery from tantrums is instantaneous once the child gets what he/she wanted. The tears immediately stop when you give him the toy, for example. In cases of tantrums, we need to determine the function—what does the child get out of this?

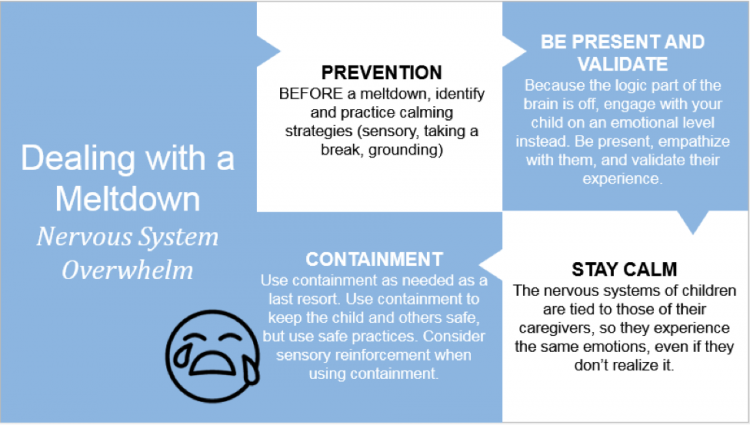

Thinking of meltdowns and tantrums in this way, our response to each will be different. For a meltdown (nervous system overload), it is best to proactively prevent them. When they do happen, solitude and reassurance are the go-to response. Use as few words as possible. During a meltdown, your child’s emotional brain takes over and the rational and processing brain is off. This includes focusing on and understanding language. They can’t comprehend explanations or logic right now, so provide calming tools to help calm their nervous systems so that their processing brains can come back online.

In contrast, remember that tantrums are intentional and deliberate; therefore, you do not want to negotiate or give in—doing so would provide reinforcement and make the tantrum more likely to happen again. Assertively and calmly explain the child’s choices and consequences, and then stick with them. For more information on dealing with tantrums, please see our webinar Tantrums and Meltdowns: Oh My!

If your child has frequent meltdowns, consider speaking with a psychotherapist or counselor about anxiety or emotion regulation issues your child might be having. Remember that a meltdown happens when the nervous system is overwhelmed. A child becomes overly anxious, scared, angry, or even happy and their emotions become intense and overtake rational thought. While adults might have coping strategies to prevent emotions from becoming overwhelming or to manage them if they do, children don’t have these resources yet, so something an adult would see as a small problem might feel really big to a child and lead to this reaction. Below are some tips for helping your child through a meltdown.

1. Prevention is the best “cure” for a meltdown. Once a child is in the meltdown state, it takes some time for them to come out of it. Preventing them from getting to that point is best. As parents, know your child’s triggers, and teach them to monitor their body in order to be able to identify when they may become overwhelmed. Help them learn how to communicate when they start to feel overwhelmed and need a break. Check in with them in situations that you know cause intense emotions, and encourage calming strategies if you see a meltdown coming on. Calming strategies can include taking breaks from the stressful situation; moving to a calm environment; using grounding techniques like mindfulness activities or wiggling fingers and toes; and using sensory tools like silly putty, a weighted blanket, or a fidget toy. Experiment to find what helps your child to feel calm BEFORE a meltdown ever happens so you know what to turn to when you need it.

2. Be present and validate the child. Sit with them as they are going through this uncomfortable experience and engage with them emotionally. Show them that you feel what they are going through and understand it. DO NOT try to problem solve, fix it, ask questions, or distract them. Name the emotions, tell them it’s okay to feel that way, and let them know it’s normal and this will pass. Some kids might prefer to be left alone during this time, and that’s okay. Just join them in the emotions they are feeling using as few words as possible—no explanations or lecturing.

3. Parents should do their best to stay calm during their child’s meltdown. The nervous systems of children are tied to those of their caregivers. When parents feel scared, the child senses this and feels scared, too. If you get angry or anxious when your child has a meltdown, it will likely make it worse. In addition, Tony Attwood, an Asperger’s expert, says that many people with autism have a sixth sense in which they are able to intuit and feel the negative emotions of others. They can be hypersensitive to others’ anger, sadness, frustration, and disappointment. So if you’re angry, even if you don’t show it, they know it.

4. Use containment techniques as a last resort if necessary to keep your child safe. If the child poses a safety threat to him or herself or others, use safe practices to contain him or her. When using containment, especially if you use it routinely, consider whether it might be giving the child reinforcing sensory stimulation. If this is the case, have other sensory-stimulating activities in the environment to reduce the need for containment.

It is possible for a child to learn that their meltdown got them some form of reinforcement, and then the behaviors may become deliberate. Once you get through the meltdown, go back to whatever tasks the child might have missed because of it so that they don’t learn that a meltdown gets them out of something, and/or have them practice and reinforce appropriate behaviors for getting attention or access to toys or activities so they don’t learn that meltdowns are an effective way to communicate what they want or need.

For more information on dealing with tantrums, please see our webinar Tantrums and Meltdowns: Oh My!